هل حانت نهاية الإخوان المسلمين في مصر؟

Is This the End of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood?

، هل سيرسل حكام مصر العسكريين أقدم منظمة إسلامية في العالم إلى مزبلة التاريخ؟

بواسطة جيليان كينيدي

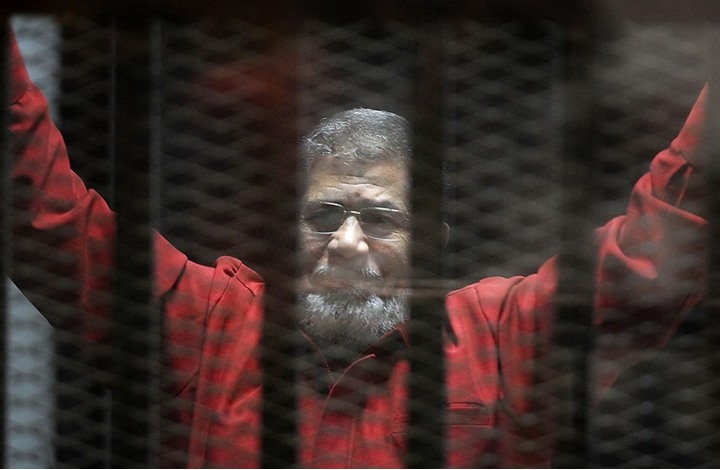

في قيظ حر قاعة محكمة قاهرية في شهر مايو، استمع محمد مرسي بحزم للقاضي أثناء تلاوته لحكم الإعدام إثر

في قيظ حر قاعة محكمة قاهرية في شهر مايو، استمع محمد مرسي بحزم للقاضي أثناء تلاوته لحكم الإعدام إثر اتهامات بالفساد والتعذيب طالت الرئيس المعزول، والتي جرت وفق المزاعم أثناء عامه الوحيد في الحكم، عام

2012. إلى جانب مرسي، وقف المئات من أقرانه الأعضاء بجماعة الإخوان المسلمين، وحكم أيضًا على الكثير

من القادة الكبار في التنظيم بالإعدام، أو بالسجن لمدد طويلة.

كذلك حكمت محكمة اليوم بالسجن مدى الحياة على الرئيس المعزول في قضية اتُهم فيها بالتآمر مع قوى أجنبية -

رغم أن مدى استمرار ذلك الحكم سيعتمد على مدى نجاح مرسي في إطالة عمره. وبعد إحالة القضية للمفتي

ا

الأكبر شوقي علام – وحكمه في القضية استشاري – لاستشارته بشأن حكم الإعدام، صدّقت نفس المحكمة اليوم

على حكم الإعدام ضدَّ مرسي

وفي ضوء هذا الحكم، هل سيرسل حكام مصر العسكريين أقدم منظمة إسلامية في العالم إلى مزبلة التاريخ؟

قد يعني مصير مرسي نهاية الإخوان المسلمين، لكن من المرجح بشكل أكبر أن التنظيم سيُدفع به إلى العزلة

السياسية خلال المستقبل القريب. واجه التنظيم حملة أمنية خطيرة منذ يوليو 2013، عندما استولى الجنرال عبد

الفتاح السيسي على السلطة عبر عزل أول رئيس مصري مدني منتخب بشكل ديمقراطي، في أعقاب ثورة شعبية

ضدَّ حكم الإخوان المسلمين.

كانت الحملة القمعية التالية، على الإخوان وتنظيمات المعارضة اليسارية، واحدة من أكثر الحملات وحشية في

التاريخ المصري. حيث لقي أكثر من 800 شخص من داعمي الإخوان المسلمين مصرعهم أثناء الاحتجاجات

المناهضة لعزل مرسي، في ميدان رابعة العدوية. تخطى ذلك المستوى من وحشية الدولة عدد قتلى ميدان

تيانانمين عام 1989، الذي بلغ 500 قتيل.

تفاقمت الأزمة إثر انقسامات حادة داخل الإخوان المسلمين، حيث أثيرت أسئلة داخل أوساط الإسلاميين بشأن

الكيفية المناسبة للتعامل مع قمع الدولة وكيفية استعادة دعم الشعب المصري، الذي دعم الكثير منه ذراع السيسي

الثقيل الذي استُخدمه عقب الإطاحة بمرسي.

انتخب السيسي، في مايو 2014، بنسبة 97 بالمئة في الانتخابات، لتعكس تلك النسبة تطلع الكثير من المصريين

للعودة إلى الاستقرار بعد أربع سنوات من الفوضى. كشفت إحصائية أجراها مركز "بيو"، في عام 2014، عن

أن حوالي 43 بالمئة من المصريين يظنون أن الزعيم الذي يتبنّى القوة هو أفضل أداة للتعامل مع التحديات

المصرية الضخمة. يبدو أن سياسات الرجل القوي قد عادت لتبقى.

في غضون ذلك، يبدو أن الإخوان المسلمين يواجهون فوضى داخلية. فالقادة الأصغر الذين احتلوا سابقًا مناصب

متوسطة في هيكل الجماعة وكانوا ذوي تأثير ضئيل في مكتب إرشاد الإخوان – وهو قمّة القيادة العليا السابقة

داخل التنظيم – قد تم تسريع تقدمهم في الأدوار القيادية. كحركة اجتماعية تتشكل من حزب سياسي ومؤسسة

خيرية وطنية، كان الإخوان المسلمين دائمًا تنظيمًا صعب التوصيف.

وكانوا مضطرين دائمًا للتعامل مع المنشقين داخليًا – سواء أكان التنظيم الجهادي الذي شكله سيد قطب، في عام

1965، أو تنظيم الجهاد الخاص بأيمن الظواهري، الذي ساهم في تنظيم الاغتيال المذاع تلفزيونيًا للرئيس أنور

السادات، في عام 1981، أو التمرد الإسلامي في التسعينيات. كان الإخوان دائمًا في قلب العقدة المستعصية

المصرية، حيث يظل دور الإسلام وسلطة الدولة غير محسوم.

تحت إكراه اللجوء للامركزية وبفعل الاعتقالات الواسعة والقادة المنفيين، يتخذ الإخوان حاليًا القرارت دون

سلطة من مكتب الإرشاد، متخذين لجانا شبابية انتخبت حديثًا لإدارة التنظيم المحظور. تشير التقارير الأخيرة

إلى أن الجيل الأقدم، الذي يقيم الكثير من أفراده حاليًا في إسطنبول (بقيادة الأمين العام للتنظيم محمود حسين)،

قلق من الخطاب العنيف للجناح الشبابي ضدَّ نظام السيسي. بينما يحرص حسين والقادة الأقدم المتشددون، مثل

محمود عزت، على الحفاظ على النهج الإصلاحي تجاه النظام، الذي تبنّته الجماعة خلال حقبة مبارك.

إلا أنه خلال الأسبوع الماضي، صرّح محمد منتصر، المتحدث الإعلامي باسم التنظيم والمقيم في القاهرة، عبر

صفحة الإخوان على موقع فيس بوك بأن التنظيم سيسعى "لاستعادة الشرعية، والقصاص للشهداء، وإعادة بناء

المجتمع المصري على أسس سليمة ومتحضرة". يشعر الكثير من القادة الأصغر بأن إستراتيجيات حقبة مبارك

عديمة الجدوى في مناخ ما بعد 2013. فدون قيادة مركزية قوية، ستعزز الرسائل المتباينة فكرة أن الإخوان

سيظلون غير مؤثرين سياسيًا، ومقوضين بفعل نقص التمويل والقيادة غير المتمرّسة.

مع ذلك، لا يجب نسيان التنظيم الإسلامي. فقد أظهر التنظيم مرونة أمام عنف الدولة تحت حكم القادة العسكريين

المتعاقبين، من ناصر وحتى مبارك. بالنسبة إلى البعض داخل التنظيم، وتحديدًا الشباب، تكمن الإجابة على

الصعوبات الحالية أمام الإخوان في الانحراف عن الماضي. حيث يريد بعض الأعضاء أن يعيدوا مواءمة أنفسهم

مع حركة شباب 6 أبريل، التنظيم الشبابي الثوري الذي كان إحدى أدوات ثورة 2011، وذلك معقول جزئيًا، في

ضوء الصلات، غير الرسمية في أغلبها، التي أقامها الإخوان في السابق مع التحالف المناهض للحرب عام

2005، واحتجاجات حركة كفاية عام 2007، والتظاهرات اليسارية والعلمانية عام 2011.

إن تمكن شباب الإخوان من الانفصال عن ضيق الأفق وتأسيس تحالف مستدام مع 6 أبريل وتنظيمات أخرى

بشكل حقيقي، قد يمثل مصدر إزعاج دائم لنظام السيسي العسكري. تتمتع تلك التنظيمات بأهداف مشتركة،

كالقضاء المستقل، والانتخابات الحرة والعادلة، وإنهاء قوانين الطواريء، وصحافة مفتوحة دون ترهيب من

الدولة. تربط تلك القضايا جميع التنظيمات المعارضة، سواء أكانت إسلامية أو علمانية.

إلا أن غياب الثقة في الإخوان المسلمين بعد عامهم في السلطة راسخ بشدّة. فخلال عام مرسي في السلطة،

أشرفت الحكومة على اعتقال النشطاء، وشنّت حملة على أصوات إعلامية رفيعة المستوى (حيث اعتقل جون

ستيوارت المصري، باسم يوسف، بشكل معلن بعد أداء فقرات تلفزيونية ساخرة من مرسي) ورفضت الحكومة

إتاحة صوت للأحزاب الشبابية الثورية في حكومة ما بعد مبارك. مع ذلك، قد تبدأ الجماهير المصرية في النظر

إلى الإخوان المسلمين بعين أكثر تعاطفًا، في ضوء حملة السيسي الأمنية على المعارضة وتأجيل الانتخابات

البرلمانية إلى أجل غير مسمى.

مع ذلك، من المرجح أن يتفاقم العنف قصير المدى. فقد فقدت سيناء لصالح تنظيم مصري تابع لتنظيم الدولة

الإسلامية (داعش) وشهدت المنطقة تصاعدًا واضحًا في العنف ضدَّ الشرطة. في غضون ذلك، تبدو الولايات

المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروبي غير مستعدين لمساءلة استبداد السيسي، بل وتبادله بالإذعان للتحالف مع السيسي

باسم محاربة التطرف. كذلك يتصاعد العنف في شبه الجزيرة العربية، ما سيشجع الجهاديين في مصر على

الأرجح.

إن كان الغرب قد تعلم أمرًا واحدًا من العقد الماضي في الشرق الأوسط، فيجب أن يكون أنه عندما يستمر استبداد

الدولة، يتعزز التجنيد لدى التنظيمات الإسلامية المتطرفة. وبينما تتم تنحية مرسي والإخوان جانبًا، سيتمسك

هؤلاء برداء القضية الإسلامية، سائرين بها نحو أعماق أكثر ظلامًا بعيدًا عن مصر. في وجه المواجهة الحادة

بين الدولة والأطراف الأخرى والانقسام الداخلي المتصاعد داخل الجماعة، ستواجه مصر على الأرجح دائرةً

دائمة التصاعد من العنف.

د. جيليان كينيدي، زميلة أبحاث زائرة بمعهد دراسات الشرق الأوسط بكلية الملك بلندن.

In the blistering heat of a Cairo courtroom in May, a resolute looking Mohammed Morsi listened as the judge announced a death sentence for charges of corruption and torture against the ousted president, which allegedly took place during his one year in power in 2012. Alongside Morsi, hundreds of his fellow Brotherhood members, many senior leaders within the organization were also assigned death sentences or long prison terms. A court also upheld a life sentence today against the ousted president in a case where he was also accused of conspiring with foreign powers—although how long that sentence will hold will depend on how successfully Morsi can prolong his life. After consultation with Grand Mufti Shawki Allam’s advisory opinion on the death sentence, the same court today confirmed the death sentence against Morsi. With this verdict, will Egypt’s military rulers consign the world’s oldest Islamist organization to the dustbin of history?

Morsi’s fate could mean the end of the Muslim Brotherhood, but it is more likely that the organization will be pushed into the political wilderness for the foreseeable future. The organization has faced a severe crackdown since July 2013 when General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi took power from Egypt’s first democratically elected president, following a popular uprising against Muslim Brotherhood rule. The subsequent clampdown on both the Brotherhood and leftist opposition groups has been one of the most brutal in Egyptian history. Over 800 Muslim Brotherhood supporters were killed during protests against Morsi’s ouster in Rabaa al-Adawiya Square. This level state brutality even exceeded the 500 death toll in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

The crisis has been compounded by serious divisions within the Brotherhood. Questions among Islamists arise over how the organization should respond to state repression and how to regain the support of the Egyptian people, many of whom support Sisi’s heavy-handedness following Morsi’s removal. Sisi was elected in May 2014 with 97 percent of the vote, marking a desire among many Egyptians to return to stability after four years of chaos. In a 2014 survey by the Pew Centre, some 43 percent of Egyptians think that a leader with a strong hand is the best way to deal with Egypt’s myriad challenges. It seems as though a return to strongman politics in Egypt is here to stay.

Decentralized and severely damaged by mass arrests and exiled leaders, the Brotherhood now makes decisions without authorization from the Guidance Bureau, with newly elected youth committees managing the banned organization. Recent reports suggest that the older generation, many of whom are now based in Istanbul (led by the Brotherhood's Secretary-General Mahmoud Hussein), are wary of the young wing’s violent rhetoric against the Sisi regime. Hussein and older hardline leaders such as Mahmoud Ezzat are eager to maintain a reformist approach to the system, which the group adopted for during the Mubarak era. However, the past week, Mohamed Montasser, the group’s Cairo-based media spokesman, stated on the Ikhwan Facebook page that the group would aim to “restore legitimacy, exact retribution for the martyrs, and rebuild Egyptian society on a sound and civilized basis.” Many younger leaders feel that Mubarak-era strategies are useless in the post-2013 environment. Without a strong central leadership, mixed messages will reinforce the idea that the Brotherhood will remain politically insignificant, undercut by a lack of finances and inexperienced leadership.

Still, the Islamist group should not be written off. The organization has shown resilience in the face of state violence under successive military leaders, from Nasser to Mubarak. For some within the organization, in particular the youth, the answer to the Brotherhood’s current difficulties lies in diverging from the past. Some members want to realign themselves with the April 6 Youth Movement, a youth revolutionary group that was instrumental in the 2011 uprising. This is not entirely implausible, given the largely informal links the Brotherhood previously forged with the 2005 Anti-War Coalition, the 2007 Kefaya protests, and leftists and secular protesters in 2011. If the Brotherhood youth can break away from single-mindedness and genuinely establish lasting alliance with April 6 and other groups, this youth alliance could be a persistent plague on Sisi’s military regime. These groups have shared goals: an independent judiciary, free and fair elections, an end to Emergency Laws, and an open press free of state intimidation. These issues link all opposition groups, whether Islamist or secular.

However, distrust of the Brotherhood after their one year in power is deeply rooted. During Morsi’s year in power, the government oversaw the arrest of activists, cracked down on high-profile media voices (Egypt’s very own Jon Stewart, Bassem Youssef was arrested in a publicized manner following satirical TV sketches mocking Morsi), and refused to give the revolutionary youth parties a voice in the post-Mubarak government. Nevertheless, the Egyptian populace may begin to view the Brotherhood in a more sympathetic light, given Sisi’s crackdown on opposition and the indefinite postponement of parliamentary elections. Still, short-term violence is likely to escalate. Sinai has been practically lost to an Egyptian affiliate of Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL) and the region has witnessed a visible upsurge in violence against the police. Meanwhile, the United States and European Union appear unwilling to question Sisi’s authoritarianism, instead trading acquiescence for Sisi’s alliance in the name of fighting extremism. Violence is also ascending across the Arabian Peninsula, which is likely to encourage jihadists in Egypt.

If the West has learned one thing from the last decade in the Middle East, it should be that when state authoritarianism persists, it encourages recruitment among extremist Islamist groups. While Morsi and the Brotherhood are being pushed aside, these extremists will grab the mantle of the Islamist cause, taking it to darker depths far beyond Egypt. In the face of unrelenting confrontation by both state and non-state actors and growing internal division within the Brotherhood, Egypt will likely face an ever-escalating cycle of violence.

Dr. Gillian Kennedy is a Visiting Research Fellow for the Institute of Middle Eastern Studies (IMES) at King's College London.

#باعشق_ترابك_ياوطن

#قناة_السويس_الجديدة_هدية_مصر_للعالم

#جيش_مصر_خط_أحمر

#جيشنا_الأول_فى_الشرق_الأوسط

#جيشي_الوحيد_فى_المنطقة_الأن

#خير_أجناد_الأرض_وأفتخر

#كوكى_عادل

#بنت_النيل

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق